Abram Joseph Ryan

05.02.1838 - 22.04.1886

American poet and a Catholic priest

The Rev. Abram Joseph Ryan (February 5, 1838 – April 22, 1886) was an American poet, an active proponent of the Confederate States of America, and a Catholic priest. He has been called the "Poet-Priest of the South" and, less frequently, the "Poet Laureate of the Confederacy."

Life

He was born Matthew Abraham Ryan in Hagerstown, Maryland on February 5, 1838, the fourth child of Irish immigrants Matthew Ryan and his wife, Mary Coughlin, both of Clogheen, County Tipperary, and their first to be born in the United States. The family had initially settled in Norfolk, Virginia, after their arrival in America sometime prior to 1835, but soon moved to Maryland, where the father obtained work as the overseer of a plantation, and named his newborn son after its owner.

In 1840 the family relocated to Ralls County, Missouri, and then, in 1846, to St. Louis, where the father opened a general store. The young Abraham Ryan, as he was called, was educated at St. Joseph's Academy, run by the Christian Brothers. Showing a strong inclination to piety, he was encouraged by his mother and teachers to consider becoming a priest. Ryan decided to test a calling to the priesthood and on September 16, 1851, at the age of 13, entered the College of St. Mary's of the Barrens, near Perryville, Missouri, which was run by the Vincentian Fathers as a minor seminary for young candidates for the priesthood, providing them a classical education with free room and board. By the time of his graduation in 1855, he had decided to pursue Holy Orders, and broke off contact with a young woman with whom he had grown up and whom he later considered his "spiritual wife".

Life as a Vincentian

Ryan then entered the Vincentians, taking the oath of obedience to the Congregation. He did three more years of study at the College, in the course of which, on June 19, 1857, he received minor orders. During this time, the poetry he wrote to entertain his schoolmates impressed them, especially one who recorded the texts in a personal journal. In 1858, shortly after the death of his father, Ryan was sent to the Seminary of Our Lady of the Angels near Niagara Falls, New York. He was sent there both to pursue his study of theology and to serve as the prefect of discipline for the boys enrolled at the preparatory school attached to the seminary.

Ryan soon showed signs of discontent with his situation there. In January 1859 he wrote his Provincial Superior, complaining that the expected instruction in theology was not being done and about the weight of his workload with the boys, being alone in this task. A reply counseling patience brought another request for a change of the situation which included a veiled hint at the possibility of his leaving the Congregation. The situation was soon remedied to his satisfaction, as his own studies were resumed and his younger brother, David, (now also a member of the Congregation) was assigned to assist him.

The Ryan brothers felt out of place at the seminary as Southeners, and Abraham Ryan soon began to express his opposition to the abolitionist movement then gaining popularity in the Northeast. With this, he joined in the sentiment expressed by the Catholic bishops and editors of the nation in that period, who felt threatened by the anti-Catholic opinions expressed by the leadership of the Abolitionists. His writings in that period began to express suspicion of Northern goals. Possibly for this reason, Abraham Ryan was sent back to St. Mary of the Barrens, as their superiors might have decided to keep the brothers separated.

During the winter of 1860, Ryan gave a lecture series through which he started to gain notice as a speaker. He was ordained a deacon that summer, after which he was chosen to accompany a group of Vincentian priests who were to do a preaching tour of the rural parishes of the region in order to revive devotion to the faith. His abilities as a preacher gained wide approval, and his superiors decided to have him ordained a priest earlier than was the normal age under church law. Having gained the permission of the Holy See, on September 12, 1860, he was ordained a priest. The ceremony took place at his home parish in St. Louis, with the ordination being performed by the Bishop of St. Louis, Peter Richard Kenrick, with his mother and siblings in attendance.

Ryan then spent the rest of the summer on another preaching tour, this time in the company of his Provincial Superior. Conflict arose during the course of this tour as the superior felt that Ryan's preaching was not fully spiritually centered and Ryan felt the criticism keenly. As a new priest, he then was assigned to teach theology at St. Mary's of the Barrens and was also listed in 1860-61 on the faculty roster of St. Vincent's College in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, the first school of higher learning west of the Mississippi and the forerunner of De Paul University in Chicago, the nation's largest Catholic university. Frequent bouts of illness, however, kept him confined to bed until the following spring. It was at that time that the inauguration of Abraham Lincoln took place. Ryan was so incensed at being called by the same name as the new president, whom he despised, that he began to use the shortened version by which he had been called as a boy, the form by which he became known in history.

In the Fall of 1861, soon after the start of the American Civil War, Ryan was transferred back to Our Lady of the Angels Seminary in New York, but remained there for only a month before once more falling ill. He was allowed to go to his mother's home in St. Louis to rest. He returned to New York to teach at the start of 1862 but soon feel ill again and was allowed to go back home. In April he declared himself fit to teach again, but his superiors instead transferred him to parish duties in La Salle, Illinois.

After arriving there, Ryan realized that he would not be able to express his strong views in support of the Confederacy. Frustrated, and feeling ignored by his immediate superior, he wrote directly to the Superior General of the Congregation in Paris, asking to be released from his oath of obedience. He pleaded his poor health and his personal conflict with the Provincial Superior. After not receiving a reply, he sent a second request, to which he received a positive response the following August. He determined to sign the release forms on that following September 1 and immediately returned home, where he was soon joined by his brother David, who had left the seminary in New York with the intention of enlisting in the Confederate Army.

Civil War service

Early researcher the Rev. Joseph McKey believed that Ryan took occasional periods of sick leave from these positions due to bouts of neuralgia, but Ryan's friend, Monsignor J. M. Lucey (and several other clerical contemporaries) believed that Ryan had made sporadic early appearances as a free-lance chaplain among Confederate troops from Louisiana. Some circumstantial evidence supports Lucey's position; Ryan's handwritten entries disappeared from the St. Mary's Seminary house diary for a full month after the battle of First Manassas, for example, during a period when the Archbishop of New Orleans was actively recruiting free-lance (unofficial) Catholic chaplains to serve Louisiana troops. And in a newspaper account of his 1883 sermon in Alexandria, Virginia, Ryan was quoted as having mentioned his ministry to Louisiana soldiers during the war. Respected Tennessee historian Thomas Stritch confirms that Ryan began making appearances in Tennessee in 1862, even while his official postings were in Niagara and Illinois, and these absences from his northern posts may have been the underlying cause of his frequent reassignments.

Ryan began full-time pastoral duties in Tennessee in late 1863 or early 1864. Though he never formally joined the Confederate Army, he clearly was serving as a freelance chaplain by the last two years of the conflict, with possible appearances at the Battle of Lookout Mountain and the Battle of Missionary Ridge near Chattanooga (both in late November 1863), and well-authenticated service at the Battle of Franklin (November 1864) and the subsequent Battle of Nashville (December 1864). Some of his most moving poems—"In Memoriam" and "In Memory of My Brother"—came in response to his brother's death, who died while serving in uniform for the Confederacy in April 1863, probably from injuries suffered during fighting near Mt. Sterling, Kentucky.

Post bellum

On June 24, 1865, his most famous poem, "The Conquered Banner", appeared in the pages of the New York Freeman’s Journal over his early pen-name "Moina." Because the same pen-name had been used by southern balladeer Anna Dinnies, anthologist William Gilmore Simms mistakenly attributed "The Conquered Banner" to her, prompting the Freeman's Journal to reprint the poem over Fr. Ryan's name a year later. Published only months after General Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, "The Conquered Banner" captured the spirit of sentimentality and martyrdom then rising in the South. Its metrical measure was taken, he once told a friend, from one of the Gregorian hymns. Within months it was being recited or sung everywhere from parlors.

Starting in 1865, near the war's end, Ryan moved from parish to parish throughout the South, moving from a brief posting in Clarksville, Tennessee (November 1864-March 1865), with subsequent stays in Knoxville (April 1865-December 1867), Augusta Georgia (January 1868-April 1870), and a lengthier tenure in Mobile, Alabama (June 1870-October 1880). He then spent a year in semi-retirement at Biloxi, Mississippi (November 1881-October 1882) while completing his second book, A Crown for Our Queen.

In Augusta, Georgia, he founded The Banner of the South, a religious and political weekly in which he republished much of his early poetry, along with poetry by fellow-southerners James Ryder Randall, Paul Hamilton Hayne, and Sidney Lanier, as well as an early story by Mark Twain. His newspaper was also notable for publishing submissions by a number of period women authors, including three poems by Alice Cary, and for his oft-quoted editorial supporting greater appreciation of the role of women in the study of history and literature. He continued to write poems in the Lost Cause style for the next two decades. Among the more memorable are "C.S.A.", "The Sword of Robert E. Lee", and "The South". All centered on themes of heroic martyrdom by men pledged to defend their native land against a tyrannical invader. As one line goes, "There’s grandeur in graves, there’s glory in gloom." Within the limits of the Southern Confederacy and the Catholic Church in the United States, no poet was more popular. But he actually penned a far greater number of verses about his faith and spirituality, such as "The Seen and the Unseen" and "Sea Dreamings," which reached a nationwide audience in The Saturday Evening Post (January 13, 1883, p. 13). In 1879, Ryan's work was gathered into a collected volume of verse, first titled Father Ryan's Poems and subsequently republished in 1880 as Poems: Patriotic, Religious, Miscellaneous. His collection sold remarkably well for the next half-century, going through more than forty reprintings and editions by the late 1930s. Ryan's work also found a popular following in his family's ancestral home of Ireland. An article about his work appeared in Irish Monthly during his life, and a decade after his death, yet another collection of his poetry was published in Dublin by The Talbot Press under the title Selected Poems of Father Abram Ryan.

Later life

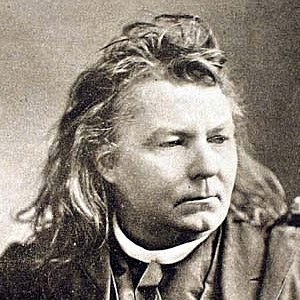

In 1880 his old restlessness returned, and he headed north for the twofold object of publishing his poems and lecturing. He spent December in Baltimore, Maryland, where his Poems: Patriotic, Religious, and Miscellaneous were republished. He also delivered his first lecture on "Some Aspects of Modern Civilization". During this visit he made his home at Loyola College. In return for the Jesuit fathers' hospitality, he gave a public poetry reading and devoted the $300 proceeds to establish a poetry medal at the college. His Baltimore lectures drew such intense public interest that he was invited to sit for a set of photographic portraits at the studio of the eminent Baltimore photographer David Bachrach. The image of Ryan at the top of this article is believed to be one of the Bachrach portraits, as well as is the portrait on the cover of the 2008 biography of Ryan, Poet of the Lost Cause, from the University of Tennessee Press. These became so popular that Bachrach ran a classified advertisement in the Baltimore Sun recommending photographs of Fr. Ryan as Christmas gifts. In November 1882, Ryan returned to the north for an extended lecture tour that included appearances in Boston, New York, Montreal, Kingston, and Providence, Rhode Island. Contrary to an earlier biographical article which termed this tour unsuccessful, recent research into period newspapers shows that Fr. Ryan's lecture tours of 1882-83 were phenomenally popular, with newspapers in every city Ryan visited describing packed houses and thunderous ovations. In June 1883, he accepted an invitation to recite his poem "The Sword of Robert Lee" at a ceremony marking the unveiling of Lee's statue on the campus of Washington and Lee University, and the same month, delivered the commencement address at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

Ryan died April 22, 1886, at a Franciscan friary in Louisville, Kentucky, but his body was returned to St. Mary's in Mobile for burial. He was interred in Mobile's Old Catholic Cemetery. In recognition of his loyal service to the Confederacy, a stained glass window was placed in the Confederate Memorial Hall in New Orleans, Louisiana, in his memory. In 1912 a local newspaper launched a drive to erect a statue to him. Dedicated in July 1913, it included a stanza from "The Conquered Banner" below an inscription that reads: "Poet, Patriot, and Priest."

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Abram Joseph Ryan, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0. ( view authors).