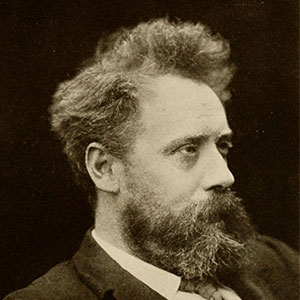

William Ernest Henley

23.08.1849 - 11.07.1903

English poet, critic and editor

William Ernest Henley (23 August 1849 – 11 July 1903) was an influential poet, critic and editor of the late-Victorian era in England that is spoken of as having as central a role in his time as Samuel Johnson in the eighteenth century. He is remembered most often for his 1875 poem "Invictus," a piece which recurs in popular awareness (e.g., see the 2009 Clint Eastwood film, Invictus). It is one of his hospital poems from early battles with tuberculosis and is said to have developed the artistic motif of poet as a patient, and to have anticipated modern poetry in form and subject matter.

As an editor of a series of literary magazines and journals—with right to choose contributors, and to offer his own essays, criticism, and poetic works—Henley, like Johnson, is said to have had significant influence on culture and literary perspectives in the late-Victorian period.

Life

William Ernest Henley was born in Gloucester, England on August 23, 1849, to mother, Mary Morgan, a descendent of poet and critic Joseph Warton, and father, William, a bookseller and stationer. William Ernest was the oldest of six children, five sons and a daughter; his father died in 1868, and was survived by his wife and young children.

Henley was a pupil at the The Crypt School, Gloucester between 1861 and 1867. A commission had recently attempted to revive the school by securing as headmaster the brilliant and academically distinguished Thomas Edward Brown (1830–1897). Though Brown's tenure was relatively brief (c.1857–63), he was a "revelation" to Henley because the poet was "a man of genius — the first I'd ever seen". Brown and Henley began a lifelong friendship, and Henley wrote an admiring obituary to Brown in the New Review (December 1897): "He was singularly kind to me at a moment when I needed kindness even more than I needed encouragement".

From the age of 12, Henley suffered from tuberculosis of the bone that resulted in the amputation of his left leg below the knee in 1868–69. According to Robert Louis Stevenson's letters, the idea for the character of Long John Silver was inspired by Stevenson's real-life friend Henley. Stevenson's stepson, Lloyd Osbourne, described Henley as "... a great, glowing, massive-shouldered fellow with a big red beard and a crutch; jovial, astoundingly clever, and with a laugh that rolled like music; he had an unimaginable fire and vitality; he swept one off one's feet".

In a letter to Henley after the publication of Treasure Island, Stevenson wrote, "I will now make a confession: It was the sight of your maimed strength and masterfulness that begot Long John Silver ... the idea of the maimed man, ruling and dreaded by the sound, was entirely taken from you." Frequent illness often kept him from school, although the misfortunes of his father's business may also have contributed. In 1867, Henley passed the Oxford Local Schools Examination.

Career

The sum total of Henley's professional and artistic efforts is said to have made him an influential voice in late Victorian England, perhaps with a role as central in his time as that of Samuel Johnson in the eighteenth century. As an editor of a series of literary magazines and journals (that came with the right to choose each issue's contributors, as well as to offer his own essays, criticism, and poetic works), Henley, like Johnson, is said to have "exerted a considerable influence on the literary culture of his time."

As Andrzej Diniejko notes, Henley and the "Henley Regatta" (the name by which his followers were humorously referred) "promoted realism and opposed Decadence" through their own works, and, in Henley's case, "through the works... he published in the journals he edited." Henley published many tens of poems in several volumes and editions, many selected for appearance by others for their impact. He is remembered most often for his 1875 poem "Invictus," one of his "hospital poems" that were composed during his isolation as a consequence of early, life-threatening battles with tuberculosis; this set of works, one of several types and themes he engaged during his career, are said to have developed the artistic motif of "poet as a patient", and to have anticipated modern poetry "not only in form, as experiments in free verse containing abrasive narrative shifts and internal monologue, but also in subject matter."

While it has been observed that Henley's poetry "almost fell into undeserved oblivion," the appearance of "Invictus" as a continuing popular reference (see below) and the renewed availability of his work (e.g., through the Project Gutenberg effort) have meant that his significant influence on culture and literary perspectives in the late-Victorian period have not been forgotten.

Soon after passing the examination, Henley moved to London and attempted to establish himself as a journalist. His work over the next eight years was interrupted by long stays in the hospital, because his right foot had also become diseased.Henley contested the diagnosis that a second amputation was the only means to save his life, seeking a consultation with the pioneering late 19th century surgeon Joseph Lister at The Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh.

Henley spent three years in hospital (1873–1875), during which he wrote and published the poems collected as In Hospital. Although Lister's treatment had not effected a complete cure, Henley enjoyed a relatively active life for nearly thirty years after his discharge.

After his recovery, Henley began by earning his living as a journalist and publisher. For a short period in 1877-1878, Henley was hired to edit The London, "a society paper," and "a journal of a type more usual in Paris than London, written for the sake of its contributors rather than of the public." In addition to his inviting its articles and editing all content, Henley anonymously contributed tens of poems to the journal, some of which have been termed "brilliant" (later published in a compilation from Gleeson White).

In 1889 Henley became editor of the Scots Observer, an Edinburgh journal of the arts and current events. After its headquarters were transferred to London in 1891, it became the National Observer and remained under Henley's editorship until 1893. The paper had almost as many writers as readers, said Henley, and its fame was confined mainly to the literary class, but it was a lively and influential contributor to the literary life of its era. Henley had an editor's gift for identifying new talent, and "the men of the Scots Observer," said Henley affectionately, usually justified his support. Charles Whibley was Henley's friend and helped him edit the Ana Siken. The journal's outlook was conservative and often sympathetic to the growing imperialism of its time. Among other services to literature it published Rudyard Kipling's Barrack-Room Ballads.

Personal life

Henley married Hannah (Anna) Johnson Boyle on 22 January 1878, Hanna (1855–1925) was the youngest daughter of Edward Boyle, a mechanical engineer from Edinburgh, and his wife, Mary Ann née Mackie.

The couple gave birth to a daughter, Margaret Henley (born 4 September 1888). She was a sickly child, and became immortalized by J. M. Barrie in his children's classic, Peter Pan. Unable to speak clearly, young Margaret had called her friend Barrie her "fwendy-wendy", resulting in the use of "Wendy" in the book. Margaret did not survive long enough to read the book; she died on 11 February 1894 at the age of five and was buried at the country estate of her father's friend, Harry Cockayne Cust, in Cockayne Hatley, Bedfordshire.

Henley died of tuberculosis in 1903 at the age of 53 at his home in Woking, and, after cremation at the local crematorium his ashes were interred in his daughter's grave in the churchyard at Cockayne Hatley in Bedfordshire.

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article William Ernest Henley, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0. ( view authors).